Mythistoria - chapter III - the great whale. at wind and weather gallery in reykjavik IS

|

Mythistoria is Latin, meaning fabulous narrative and tall tale.

(Scroll down for text by Shauna Laurel Jones) This site specific installation at the artist run Wind and Weather gallery in Reykjavik is the 3rd in a series of window gallery projects I have created since 2013. However it began in Reykjavik at a residency at SIM in 2008 when I had a dream about a whale that was very determined about saying something to me. So to find out more I did drawings about whales, researching their mythology and listening to their songs at the residency. One of these whales was exhibited in a small window gallery in Kaffifelagid Kafe. This work has since been exhibited in various forms at Window Box in Oslo (NO)(2013) and at Studio 17 in Stavanger (NO) (2015) where I have expanded on my exploration of this story of the “underworld” in the ocean. The Whale is an animal that holds mythological power and an ancient creature that was here at the beginning of time. Whales have seen, felt and heard everything. Once they where land-animals, slowly developing to be sea-creatures. Whales are the storytellers and keepers, communicating ancient stories and current events. We are the listeners. In mythology, as with biology and ecology, all creatures small and large hold equal importance in the greater story. In this work I explore the underwater mythological stories of the ocean and creatures such as whales, frog, fish, plankton and octopus. Mythistoria is a site-specific work using wall collage with cut-out drawings and painting with black ink on the window glass. |

Dream-whales and deep listening

By Shauna Laurel Jones

Michelle Henning had a whale, which Otto Neurath once had before her.[i]

Neurath’s whale was hypothetical, but huge; its bones were suspended from the ceiling of an unknown gallery, hung neutrally with neither cause nor context, testament to the awe an impressive museum object is meant to stir in the beholder.

When Henning excavated that whale from Neurath’s 1933 essay—written to critique museological trends towards isolating natural history objects from their ecological and social frameworks—she reanimated it in the language of Latour. And then the whale (as Neurath would have wanted) ceased to arrive in the gallery as a pre-existing thing, but was created at the meeting with its viewers: a phenomenological whale, an intersubjective whale. But Henning also had this to say: “Alive,” she wrote, “it is a beast with its own purposes, its own intentions, its own unfathomable world.”[ii]

David Rothenberg had a whale who was intersubjective and alive, one of the humpbacks he courted with his clarinet via underwater speakers, the humpbacks he hoped would sing along with him. And when one did, the “strange interspecies music” rang out “in a world somewhere between human and whale, as we [made] sounds together that no one species could produce on its own.”[iii] Yet because Rothenberg’s whales had their own purposes and their own deep world (which was for them, of course, not unfathomable), they more often eluded the clarinettist at the surface, leaving him to continue playing a solo I imagine must have been mournful, full of unrequited longing.

Somewhere between the constellation of Neurath’s, Henning’s, and Rothenberg’s whales, I imagine, is Tanja Thorjussen’s whale, the creature who came to her in a dream and whom she went on to exhibit in Reykjavík, Oslo, Stavanger, and then Reykjavík again. For Thorjussen’s dream-whale was impressive and mystical in its isolated enormity; was created through the meeting with its dreamer, yet possessor of its own intentions; was sonically present but physically elusive, evoker of the practise of ‘deep listening’ “that encourages us all to pay deeper, slower attention to the world of sounds around us.”[iv] The world of sounds—and the voices of creatures.

The dream-whale swam up to its dreamer close, so close that Tanja could only remember its eye, feel its essence rather than ascertain its species. It invoked ancient mythology, but made no reference to Jonah and his whale, or the whale-monster Cetus that almost swallowed Andromeda. It certainly did not mention its having any place in Icelandic folklore, where whales “were said to be consciously malevolent, and huge enough to take a whole ship in their jaws.”[v] No, nothing so noxious! Instead, it told of its own myths, “more visual and vocal than a human story,” Tanja said.

Perhaps it was not Thorjussen’s whale; perhaps Tanja was rather, for a time, the whale’s human.

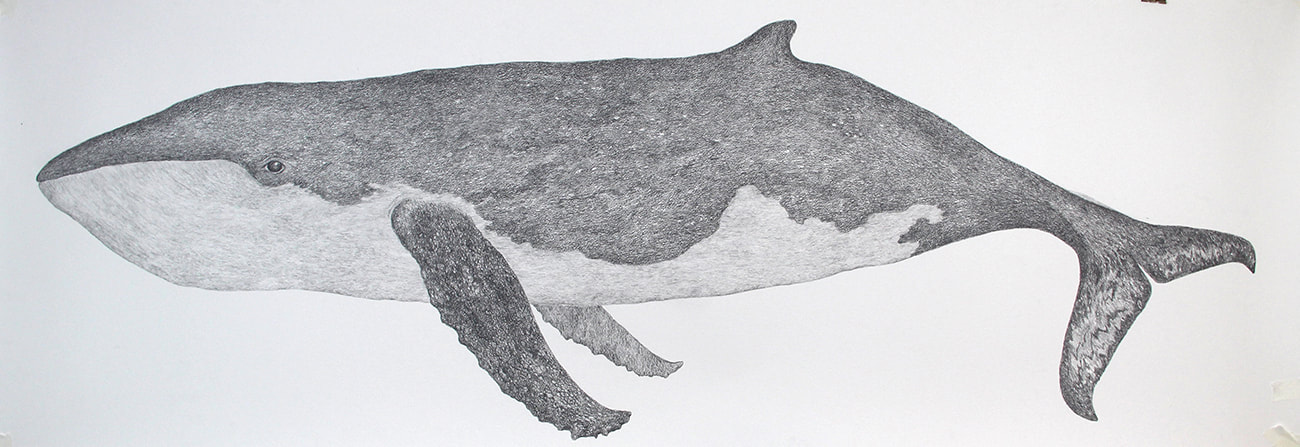

When I encountered that great whale, the whale who had, on another plane, claimed Tanja as its own, it hung in a window in downtown Reykjavík in Wind and Weather Gallery, accessible to viewers only from the outside. Tanja had rendered it meticulously, texturally, in pencil on paper, shown it in profile swimming across a white page blank save for a graceful trail of tiny bubbles, accurate and solitary like a natural history illustration. Other creatures floated in similar isolation nearby: smaller whales; a goby fish swimming above the caldera of a volcano; a magical hybrid somewhere between puffer-, lion-, and anglerfish crossed with kelp or coral; a globular mass of not-quite-identifiable oceanomorphic forms. An octopus on its own page, in its own frame. But the eye of the great whale, lovingly rendered and lovingly communicative, relatable, left no question as to who the primary subject of the exhibition was meant to be.

Standing there on the street, I photographed that whale through the window, with consideration as well to the reflection in the glass that superimposed buildings and street lamps of downtown Reykjavík over the captive sea creatures. I smiled, remembering Tanja teasing me some weeks before as I photographed reflections in the glass over Emma Kunz’s mystical drawings, taken as I was by the interplay between the geometric forms on paper and the framed works on the adjacent wall, the circle of spotlights on the ceiling. But in front of the whale, with the layers of the reflection, the glass, and representation itself between us, I also thought of Rothenberg and his longing to connect musically and meaningfully with wild creatures (be they cetacean, avian, or insect), the longing to cross that divide between ourselves and other species. There is a loneliness that such longing brings about.

Mythistoria is not about loneliness, however, but rather about the connection between the dream-whale and its human dreamer. About the invitation that whale extended to Tanja to explore the real, imagined, and mythological depths of the (dream‑)ecology from whence it came. At the fore of talk about whales in the North Atlantic at the moment is the recent announcement that no whales—fin, minke, or otherwise—will be killed in Icelandic waters in the summer of 2019, the first such hiatus in seventeen years.[vi] That is to be celebrated, certainly. But let that celebration begin with them, in their voices. Now that the cultural lives of cetaceans and other animals have finally been recognised by the scientific community as not only a real phenomenon but also essential in wildlife conservation,[vii] perhaps there is reason to be hopeful that we will learn (or is it relearn?) to open channels of cross-cultural exchange.

Or, at least, that we will open ourselves, as Thorjussen does, to accepting messages from the natural world when those messages are sent.

[i] Michelle Henning, “Neurath’s whale,” in The Afterlives of Animals: A Museum Menagerie, edited by Samuel J. M. M. Alberti (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2011), pp. 151–168.

[ii] Henning 2011, p. 156.

[iii] David Rothenberg, “How to make music with a whale,” New York Times, 5 October 2014. Retrieved from https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/10/05/how-to-make-music-with-a-whale/

[iv] Rothenberg 2014.

[v] Jacqueline Simpson, Icelandic Folktales and Legends (Stroud, UK: Tempus Publishing, 2004), p. 57.

[vi] “Iceland will skip whaling this year,” phys.org, 27 June 2019. Retrieved from https://phys.org/news/2019-06-iceland-whaling-year-company.html

[vii] “Conservation implications of animal culture and social complexity,” CMS (Convention on Migratory Species), 2017. UNEP/CMS/Resolution 11.23 (Rev. COP12). Retrieved from https://www.cms.int/en/document/conservation-implications-animal-culture-and-social-complexity-0

By Shauna Laurel Jones

Michelle Henning had a whale, which Otto Neurath once had before her.[i]

Neurath’s whale was hypothetical, but huge; its bones were suspended from the ceiling of an unknown gallery, hung neutrally with neither cause nor context, testament to the awe an impressive museum object is meant to stir in the beholder.

When Henning excavated that whale from Neurath’s 1933 essay—written to critique museological trends towards isolating natural history objects from their ecological and social frameworks—she reanimated it in the language of Latour. And then the whale (as Neurath would have wanted) ceased to arrive in the gallery as a pre-existing thing, but was created at the meeting with its viewers: a phenomenological whale, an intersubjective whale. But Henning also had this to say: “Alive,” she wrote, “it is a beast with its own purposes, its own intentions, its own unfathomable world.”[ii]

David Rothenberg had a whale who was intersubjective and alive, one of the humpbacks he courted with his clarinet via underwater speakers, the humpbacks he hoped would sing along with him. And when one did, the “strange interspecies music” rang out “in a world somewhere between human and whale, as we [made] sounds together that no one species could produce on its own.”[iii] Yet because Rothenberg’s whales had their own purposes and their own deep world (which was for them, of course, not unfathomable), they more often eluded the clarinettist at the surface, leaving him to continue playing a solo I imagine must have been mournful, full of unrequited longing.

Somewhere between the constellation of Neurath’s, Henning’s, and Rothenberg’s whales, I imagine, is Tanja Thorjussen’s whale, the creature who came to her in a dream and whom she went on to exhibit in Reykjavík, Oslo, Stavanger, and then Reykjavík again. For Thorjussen’s dream-whale was impressive and mystical in its isolated enormity; was created through the meeting with its dreamer, yet possessor of its own intentions; was sonically present but physically elusive, evoker of the practise of ‘deep listening’ “that encourages us all to pay deeper, slower attention to the world of sounds around us.”[iv] The world of sounds—and the voices of creatures.

The dream-whale swam up to its dreamer close, so close that Tanja could only remember its eye, feel its essence rather than ascertain its species. It invoked ancient mythology, but made no reference to Jonah and his whale, or the whale-monster Cetus that almost swallowed Andromeda. It certainly did not mention its having any place in Icelandic folklore, where whales “were said to be consciously malevolent, and huge enough to take a whole ship in their jaws.”[v] No, nothing so noxious! Instead, it told of its own myths, “more visual and vocal than a human story,” Tanja said.

Perhaps it was not Thorjussen’s whale; perhaps Tanja was rather, for a time, the whale’s human.

When I encountered that great whale, the whale who had, on another plane, claimed Tanja as its own, it hung in a window in downtown Reykjavík in Wind and Weather Gallery, accessible to viewers only from the outside. Tanja had rendered it meticulously, texturally, in pencil on paper, shown it in profile swimming across a white page blank save for a graceful trail of tiny bubbles, accurate and solitary like a natural history illustration. Other creatures floated in similar isolation nearby: smaller whales; a goby fish swimming above the caldera of a volcano; a magical hybrid somewhere between puffer-, lion-, and anglerfish crossed with kelp or coral; a globular mass of not-quite-identifiable oceanomorphic forms. An octopus on its own page, in its own frame. But the eye of the great whale, lovingly rendered and lovingly communicative, relatable, left no question as to who the primary subject of the exhibition was meant to be.

Standing there on the street, I photographed that whale through the window, with consideration as well to the reflection in the glass that superimposed buildings and street lamps of downtown Reykjavík over the captive sea creatures. I smiled, remembering Tanja teasing me some weeks before as I photographed reflections in the glass over Emma Kunz’s mystical drawings, taken as I was by the interplay between the geometric forms on paper and the framed works on the adjacent wall, the circle of spotlights on the ceiling. But in front of the whale, with the layers of the reflection, the glass, and representation itself between us, I also thought of Rothenberg and his longing to connect musically and meaningfully with wild creatures (be they cetacean, avian, or insect), the longing to cross that divide between ourselves and other species. There is a loneliness that such longing brings about.

Mythistoria is not about loneliness, however, but rather about the connection between the dream-whale and its human dreamer. About the invitation that whale extended to Tanja to explore the real, imagined, and mythological depths of the (dream‑)ecology from whence it came. At the fore of talk about whales in the North Atlantic at the moment is the recent announcement that no whales—fin, minke, or otherwise—will be killed in Icelandic waters in the summer of 2019, the first such hiatus in seventeen years.[vi] That is to be celebrated, certainly. But let that celebration begin with them, in their voices. Now that the cultural lives of cetaceans and other animals have finally been recognised by the scientific community as not only a real phenomenon but also essential in wildlife conservation,[vii] perhaps there is reason to be hopeful that we will learn (or is it relearn?) to open channels of cross-cultural exchange.

Or, at least, that we will open ourselves, as Thorjussen does, to accepting messages from the natural world when those messages are sent.

[i] Michelle Henning, “Neurath’s whale,” in The Afterlives of Animals: A Museum Menagerie, edited by Samuel J. M. M. Alberti (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2011), pp. 151–168.

[ii] Henning 2011, p. 156.

[iii] David Rothenberg, “How to make music with a whale,” New York Times, 5 October 2014. Retrieved from https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/10/05/how-to-make-music-with-a-whale/

[iv] Rothenberg 2014.

[v] Jacqueline Simpson, Icelandic Folktales and Legends (Stroud, UK: Tempus Publishing, 2004), p. 57.

[vi] “Iceland will skip whaling this year,” phys.org, 27 June 2019. Retrieved from https://phys.org/news/2019-06-iceland-whaling-year-company.html

[vii] “Conservation implications of animal culture and social complexity,” CMS (Convention on Migratory Species), 2017. UNEP/CMS/Resolution 11.23 (Rev. COP12). Retrieved from https://www.cms.int/en/document/conservation-implications-animal-culture-and-social-complexity-0